BOCES: A History

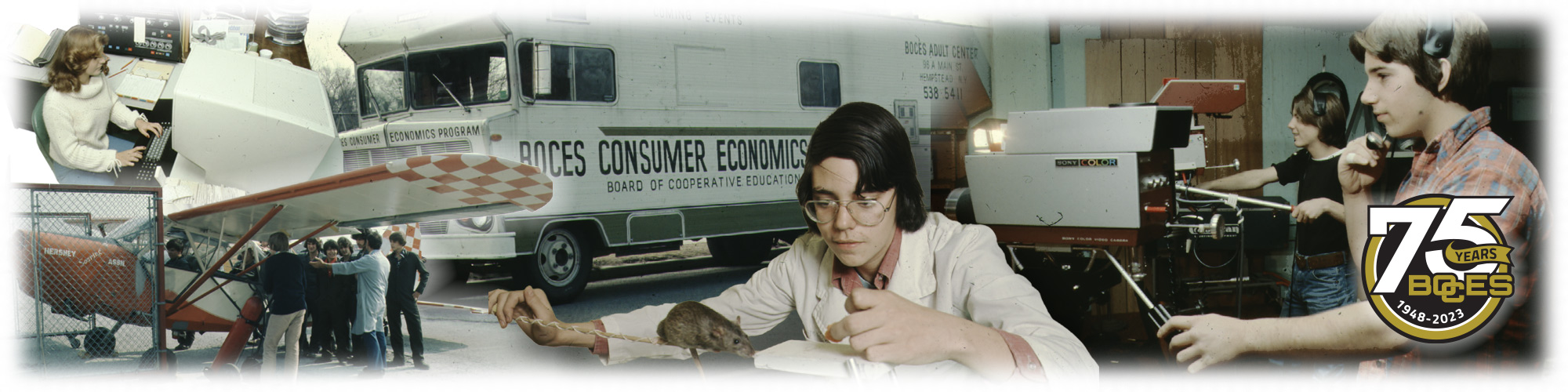

The Boards of Cooperative Educational Services (BOCES) are public organizations created by the New York State Legislature in 1948 as a way for local school districts to collaborate on educational offerings while reducing their individual expenses.

Based in Section 1950 of Education Law, BOCES were meant to be a temporary arrangement to expand equal educational opportunity in small, rural school districts where services otherwise would be uneconomical, inefficient or unavailable. But the new model caught on across New York, and has greatly expanded in scope and impact over the years.

Today, New York state’s 37 BOCES are incubators of innovation, continually developing new programs and services to meet the changing needs of students. BOCES of New York State takes pride as it marks this 75th anniversary and reflects on the challenges and opportunities that have shaped the history of the BOCES system. We are honored to have received recognition from both the Governor’s office and the state Senate for this significant milestone anniversary.

The first 25 years

1948-1973

BOCES grew rapidly in its first quarter-century from a few small pilot programs to a massive statewide network. Within a single decade, there were 82 BOCES across New York state, most of which were organized at the county level. More populous counties, like Westchester, boasted more than one BOCES. The state’s largest school districts (the “Big Five”) operated outside of the BOCES system, and continue to do so today.

Early BOCES programs were like startups, often running programs and services out of small offices or borrowed facilities with few employees. The focus was highly localized in nature, providing “supply teachers” and other core educational services to only a few districts at a time.

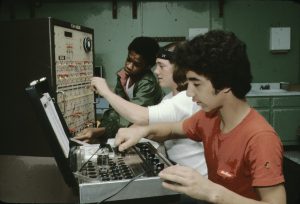

By the mid-1950s, BOCES had branched out into vocational education, as a booming post-war economy spurred demand for skilled laborers and technological advances opened new opportunities in industry. BOCES also came to the forefront as qualified providers of services for students with disabilities that many individual schools or districts could not offer.

While these two programs were very different in nature, both underscored a fundamental strength of the BOCES system: the ability to specialize and centralize services, rather than each individual school district replicating a host of complex programs.

Legislation in the 1950s and ‘60s further enhanced BOCES’ ability to grow. By 1955, BOCES were granted the right to rent facilities, and to extend membership to union free school districts. A decade later, BOCES were given the ability to purchase land and construct facilities with voter approval, and to enter into cross-contracts with one another. Services continued to be added, including adult education, professional development for teachers, summer school and a host of other offerings.

But this growth brought new scrutiny. A 1973 report noted that BOCES was still operating under a temporary legal structure, while assuming a “seemingly new role as a permanent and integral part of the public secondary education system in New York” that functioned as “unique and powerful units of government.”

BOCES was at a crossroads.

Change and consolidation

1974-1998

Just as many public school districts centralized during the 1970s and 1980s, so too did BOCES. Their numbers shrunk, as they consolidated and formed many of the cross-county coalitions we see today. By 1978 there were only 44 BOCES – about half from two decades earlier – but they still served nearly every school district in the state.

Offerings continued to grow. In the 1980s and 1990s, BOCES added adult education, distance learning and alternative high school programs. Services expanded outside the classroom to include professional and management services and technology support. Far beyond the “supply teacher” model of its origins, BOCES offered financial planning, policy development, library management, textbook purchasing, communications and a host of other services to support school districts in their region.

However, federal funding for education that began to drop in the late 1970s and remained restrained throughout the 1980s and 1990s left many BOCES facing budget and program cuts. Changing social expectations questioned the value of vocational education, while federal and state legislation mandating a free and appropriate public education to pupils with disabilities put BOCES programs under the microscope.

''Funding for Boces [sic] programs throughout the state will drop from $80 million to $30 million; that loss of $50 million represents an enormous reduction in capital for us,'' one BOCES assistant superintendent told the New York Times in 1982, adding that vocational training courses were heavily dependent on the latest technological advances. ''One of the few active job markets right now is word processing,” he said, “but you must have the latest equipment to train these students or their skills won't be of any use to them when they graduate.''

Despite these challenges, BOCES persevered, weathering these challenges to further establish themselves as a valued and influential piece of New York state’s system of public education — no longer just regional agencies, but vital conduits between local school districts and the state Education Department. By 1998, when BOCES marked its 50th anniversary, The New York Times noted that “in its 50th year, Boces has parlayed its expertise … to emerge as a leading player in academic programs that affect the broad majority of public-school students.”

The new century

1999-2023

The dawn of the 21st century saw still more challenges for BOCES, as the state’s public education system sought to reinvent itself in many ways. Students entering high school in 1999 were the first to be required to take Regents in four core courses, and academic rigor for all students continued to be a focus over the ensuing decades. By 2003, the number of required Regents was increased to five.

At the time, not all BOCES courses generated Regents credit, prompting BOCES leaders to become forceful advocates for their students and programs. One BOCES superintendent told the New York Times in 1999 that “the new Regents requirements set by the state are so academically oriented that many school districts have become reluctant to send their kids to to career ed programs at BOCES."

It would be another decade before a career and technical education (CTE) pathway was established, offering CTE students the opportunity to demonstrate their mastery of a hands-on discipline in addition to their academic ability. BOCES increasingly made it clear that vocational education no longer meant “the end of a student’s schooling,” as one newspaper article observed. BOCES graduates were going on to college more and more, thanks in part to partnerships developed between many BOCES and colleges in their regions.

Today, BOCES students study subjects such as solar engineering, drone aviation, video game design and electric vehicle tech. This never could have been imagined in 1948 when the state Legislature first authorized BOCES to be chartered. BOCES have also become major employers in their regions, providing jobs for more than 31,000 New Yorkers. What started as a temporary system to provide supply teachers has grown into a statewide network educating more than 62,000 students each year.

As services have grown beyond simple instructional support, BOCES have evolved into models of cooperative service, saving school districts millions of dollars each year through cooperative purchasing agreements, and providing job training to employees of nearly 500 businesses across the state. BOCES connect their students to unparalleled opportunities in the workforce and higher education, with more than 2,000 articulation agreements to colleges and universities, and more than 17,000 college credits earned by BOCES students each year.

The future: 2023 and beyond

Like all histories, this narrative is incomplete. History is still being written. But this attempt to trace the history of New York’s ever-changing coalition of BOCES reveals what has often been said: if the BOCES did not exist, someone would have to invent them. As we mark this 75th anniversary, the statement has never been more true. We look forward to a bright future and another 75 years of educational growth and innovation.

You must be logged in to post a comment.